Geometric Identity

each into the other are identical.

Because a number is not a geometric element, and a geometric element is not a number,

Numerical equality and geometric identity are distinct and disjoint states.

By extension, inequality and inidentity are also distinct and disjoint states.

We explore how we may establish whether or not

“properly geometric” intervals are the same:

that is, whether or not they are identical.

And, we can immediately state that

Geometric comparisons are made exclusively and without exception by projection,

strictly constrained by conditions of incidence.

Broadly put, constructions that project into each other are geometrically identical.

Such constructions are geometrically indistinguishable,

as they cannot be “told apart” by geometric means.

Thus, in this context,

being, “the same”, or, ”different”,

categorically do not

imply, “equality”,

or, “inequality”,

for we do not have here, or anywhere in

Projective Geometry, to do with magnitude:

we have to do only with

elementary incidence.

Some may prefer the term, “Equivalence”.

This page is about Geometric Identity, or

Equivalence.

Geometric Inidentity is covered here.

We will need the following facts:

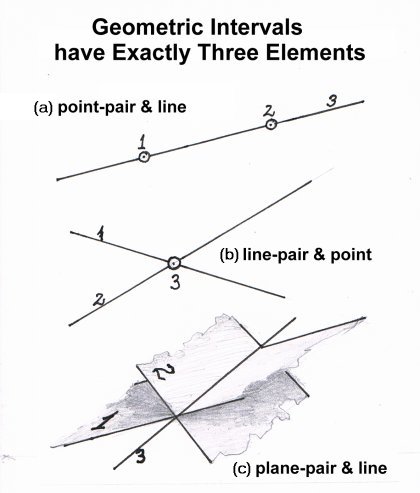

For a geometric interval to exist at all,

there must be

a proper incidence of exactly three elements.

Recalling that

geometric elements

are distinguished only by their qualities,

two of the three elements

of an interval

have the same quality,

different from

the quality of the third.

Quite unlike elements,

which have no ends,

an interval has two ends,

comprised of the two elements

with the

same quality.

For example, because

one point with one line through it

involves just two elements,

no interval is formed either

on that line, or in that point.

Hence, two points on a line are required to

form an interval on that line.

In fact,

exactly two intervals are thus formed

– and their ends

are just these two points.

- An interval of type (a) is an interpunctual interval

- (i.e., between two end-points on a line).

- An interval of type (b) is an interlinear interval

- (i.e., between two end-lines on a point and a plane).

- An interval of type (c) is an interplanar interval

- (i.e., between two end-planes on a line).

In fact, it might altogether be better to speak of interels rather than of intervals, because inter-vals are between numerical values, but we want that which falls between geometric elements, not between numbers - so, inter-els!

Projective Comparison of Intervals on Coplanar Lines

“Perspectivity” and “Projectivity”

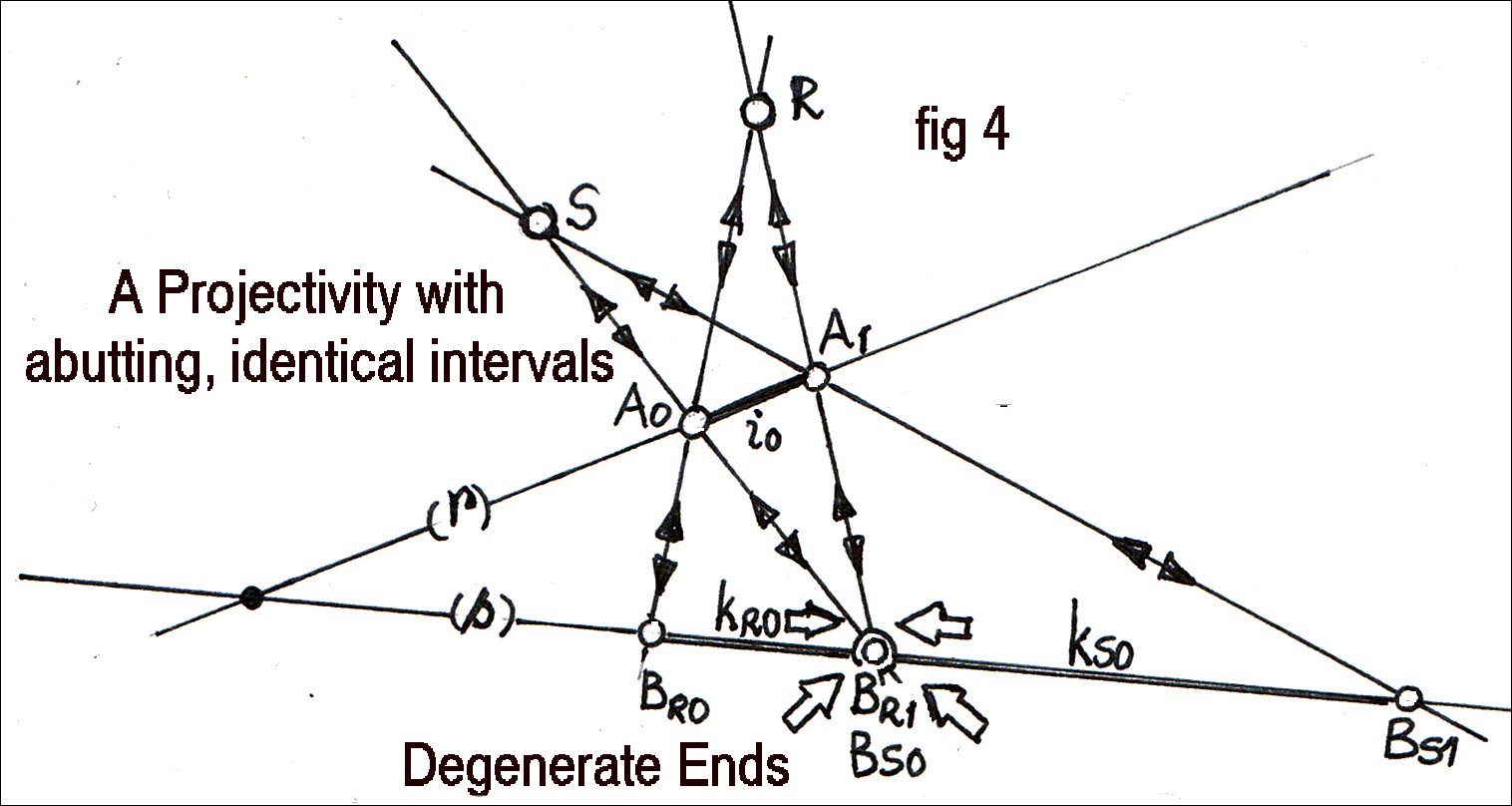

A profoundly important special case, illustrated below, arises if point BR1 degenerates into point BS0, on line s, so that intervals kR0 and kS0 “abut” – that is to say, the intervals neither separate nor overlap. In the instance above, the right end of the left interval would become ‘one’ with the left end of the right interval—which should remind us that, while elements do not have ends, intervals do. In this case, these ends are points, so these intervals are interpunctual intervals. There are also interlinear intervals, and interplanar intervals.

This, together with iteration, can be used to construct a chain of identical intervals on a line, which might serve as a sort of projective gradation, or scale — but one must take great care not to construe from it that the intervals have size, least of all equal size.

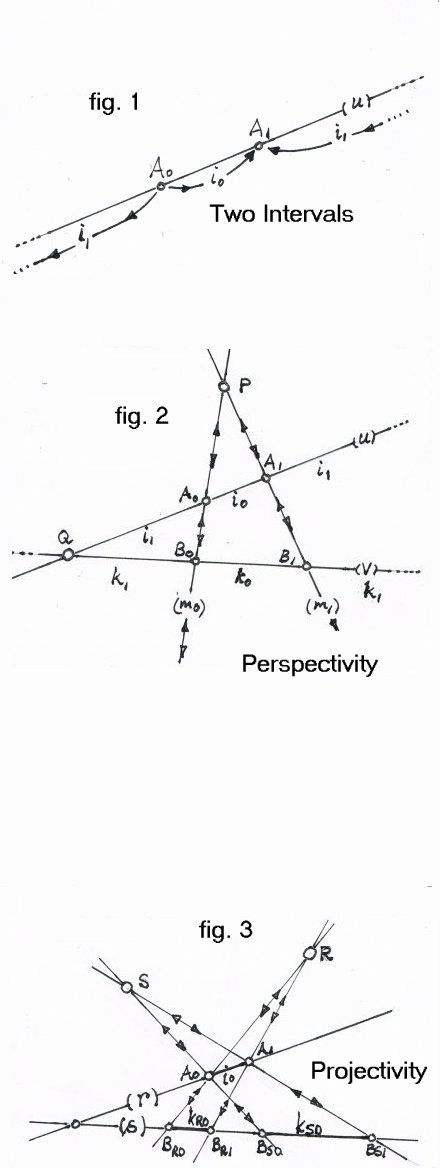

Let A0 lie to the left of A1 from the observer's vantage. Then, interval i0, ‘between’ A0 and A1, lies to the right of A0, and the second interval, i1, ‘between’ A0 and A1, lies to the left of A0, continuing leftwards to the right of A1 (because lines have no ends).

Note that the intervals are here distinguished by their senses (‘leftwards/rightwards’), not by direction – which is the same for both intervals: a sense has an opposite: a direction has not.

Similarly, let points B0 and B1, on a second line, v,

form two intervals, k0 and k1, on that line (fig. 2).

For the intervals on line u, to be geometrically identical

to those on line v,

corresponding end-points of these intervals must project centrally, from point P, say, mutually into each other.

That is, A0 on u must project into B0 on v, via line m0, say, and vice versa, and A1 on u must project into B1 on v, via line m1, say, and vice versa.

This immediately requires that

all four end-points lie on the same plane,

and, if they do that,

then lines u and v must have this plane in common,

so must also have a point (Q, say), in common.

The foregoing is

a perspectivity,

which is a range of points centrally projected

directly from one line to another,

and clearly, from the above,

its lines and points are necessarily coplanar.

We see that whenever we have one perspectivity, we must have two.

Here, we have one in point P, and another in point Q. They come in pairs.

Next, consider two lines, r and s

and two points, R and S,

all in a plane σ (fig. 3).

Points A0 and A1, on line r, form two intervals, i0 and i1, on that line.

Now, let both R and S project points A0 & A1 in line r, into points BR0 & BR1, and BS0 & BS1, in line s, which forms two pairs of intervals, kS0 & kS1, and kR0 & kR1, in line s.

Since intervals kRn & kSn are “perspectivities” of a single common interval, in, they are each geometrically identical to that common interval, and are, therefore, identical to each other.

A double projective comparison,

such as this, of two intervals

by indirection via a third, is

a projectivity.

“Lincoln” (Daniel Day-Lewis) on

Euclid's First Common Notion.

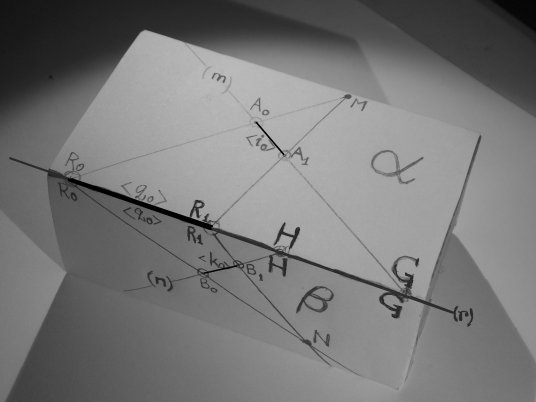

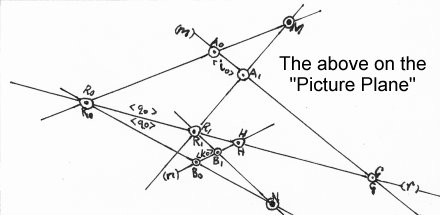

Projective Comparison of Skew (i.e., non-coplanar) Intervals

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

If two lines, say m and n, are skew to each other, they have no condition of incidence, with the result that intervals on these lines cannot be compared by single-stage, central projection—but they can be compared by two-stage, central projection to, and from, a third interval on an intermediate line, say r.

That is to say, by a projectivity.

This works because, while skew lines cannot be incident, the planes (here, α and β) in or on which they lie must be – in a line.And this line then serves as our

intermediate (here, r) for the two perspectivities carried by the two

incident planes.

Accordingly, in the picture alongside (fig. 4), we see that we have two perspectivities on two planes, with one perspectivity (from point M) on the ‘top’ plane, α, containing lines m and r, and the other (from N), on the ‘side’ plane, β, containing lines n and r,

so that the intermediate line, r, is the incidence of the planes α and β, and the skew intervals i[0,1] and k[0,1] are each compared with the same, intermediate intervals q[0,1], in that intermediate line.

Note that line m on plane α meets line r in point G, distinct from point H, in which line n on plane β meets line r. This confirms that lines m and n are indeed skew to each other.

A Note on Absolute Size and Equality, with reference to Figure 4

If the intervals i[0,1] and k[0,1] (fig. 4) are to have absolute size and to be ‘equal’ to each other in the Euclidean sense,

then in order to satisfy the conditions assumed necessary [ * ] for “parallel projection”

and for the Conflation of Units with Geometric

Elements (Calibration),

the

quadrilaterals R0R1A1A0, and R0R1B1B0,

would have

to be parallelograms,

and, for that,

points M, N, G and H would ALL have to lie on a plane in/at the infinite,

which in particular would require

points G and H to lie together at the infinite.

.jpg)

However,

since lines m and n

are by definition skew, only one of points G and H can so lie,

because,

(1) as is clear in fig. 4, they are distinct, and,

(2) a line can have just one point in common with a plane,

—unless that line (here, line r) lies in that plane (here, the plane at ∞) **,

but, if r does so lie, along with points M and N, then all the participant elements lie on that plane, including the lines m and n

which, because they are coplanar, cannot be skew.

We conclude that

it is always possible to compare skew intervals projectively

for geometric identity,

but never possible to compare skew intervals

projectively

for numerical equality.

The often-twinned assumptions that

Spatial size is (1) absolute, and (2) independent of both orientation and disposition

are fundamental to the Euclideo-Newtonian Dogma.

It should be clear from the foregoing that they are just that—assumptions.

We have considered identity of intervals made by point-pairs on lines. (type a, above)

We would need also to consider identity of intervals made by line-pairs on points, (type b)

and to consider identity of intervals made by plane-pairs on lines. (type c)